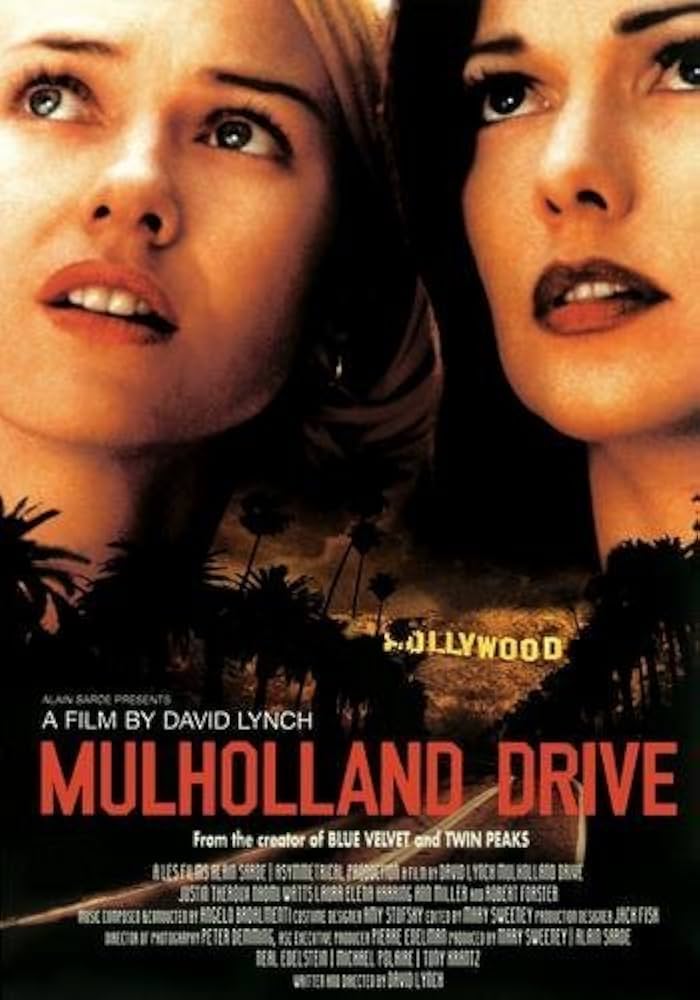

Review

This is one of those movies that doesn’t just stick in your head—it burrows in. The experience of watching it is so much stranger, heavier, and harder to pin down than a number can capture. It’s like a dream that makes perfect sense while you’re in it, only to fall apart when you try to explain it out loud. But instead of fading, it lingers. The confusion becomes part of the memory, and the memory keeps replaying itself until you start to wonder if you actually lived it. That’s the level we’re talking about here.

On the surface, the movie looks like it’s playing the usual game of Hollywood mystery. Bright-eyed actress comes to L.A. chasing her dreams, stumbles into something dark, gets tangled up with strange characters. You think you’ve seen that before, but Lynch flips it inside out until the bones of the story don’t look like anything familiar. The narrative structure is slippery, fragmented, constantly undercutting itself. Normally I hate when films lean on “dream logic” as an excuse to not make sense—it feels cheap, like a gimmick—but here it’s completely earned. The disorientation doesn’t feel like a trick. It feels essential.

Naomi Watts is the anchor that makes all this surreal chaos hit so hard. Her performance is honestly legendary, and I don’t use that word lightly. She starts out playing this almost parodic version of the Hollywood ingénue—so sweet and bubbly that it’s hard to take seriously. Then the audition scene comes, and suddenly you realize you’re watching one of the most unnerving transformations an actor has ever pulled off. It’s not just that she’s convincing—it’s that you can’t reconcile the two performances as the same person. And that split in her character mirrors the whole film’s split reality. Every time the movie shifts, she becomes someone new, and yet it all still feels connected. It’s unreal.

The supporting characters all add to that same uncanny texture. Laura Harring’s Rita is more cipher than person, but that’s what makes her effective—she’s mystery incarnate, a blank slate onto which the film projects fear, desire, and dread. The bit players too—the cowboy, the director, the hitman—each of them feel larger than their screen time, like echoes from a nightmare you can’t quite remember but know you’ve had before. Every scene feels haunted by something just off-screen.

What really elevates the film, though, is the atmosphere. Lynch is unmatched when it comes to pulling dread out of ordinary spaces. A diner, a living room, a theater—they all feel wrong. Not in the obvious horror-movie way, with blood and shadows, but in this subtle, humming way that makes your stomach turn. The diner scene especially—it’s two guys talking, nothing flashy, and yet it’s one of the scariest sequences ever put on film. You sit there waiting for something awful, and when it comes, it’s almost nothing. But the build-up rewires your brain so that “almost nothing” lands like a bomb.

And then there’s Club Silencio, which is maybe the most perfect encapsulation of the whole film’s power. “No hay banda”—there is no band. The music you hear isn’t real. It’s a recording. Everything you think you’re experiencing is fake, but your tears are real. That’s Lynch in a nutshell: creating moments that feel more authentic in their artificiality than most “realistic” movies ever achieve.

It’s not a film that explains itself, and that’s why it lasts. If it gave you answers, you’d move on. Instead, it leaves you in pieces, puzzling over images, haunted by feelings, unsettled in a way you can’t shake. It’s Hollywood satire, psychological horror, tragic romance, and surreal fever dream all at once. And somehow, against all odds, it works.

That’s why it’s not just a favorite—it’s a benchmark. The kind of movie that makes almost everything else look small in comparison. Absolutely untouchable. 10/10.

Leave a Reply